The 'Lost Art" of Breathing Impacts Sleep and Resilience

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Breathing is something we take for granted unless we have respiratory problems or are sick or worried about the coronavirus, which attacks the lungs. In the new book "Breath," my guest, journalist James Nestor, writes about many aspects of how we breathe and how we can train ourselves to breathe in ways that may improve our health and the quality of our sleep and decrease anxiety. He reports on why mouth breathing is related to snoring, sleep apnea and other problems, what the nose has that the mouth doesn't, different breathing techniques to destress, reduce blood pressure and balance the nervous system, and how free divers train to expand their lung capacity so that they can dive deep and stay underwater for up to 12 minutes on one breath.

When possible, Nestor's tried what he's written about, including participating in an experiment at Stanford in which his nose was completely plugged for days to test the impact of breathing solely through the mouth. The results were fascinating, but the experience of total mouth breathing was unpleasant and disrupted his sleep. Nestor is also the author of a previous book called "Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science, And What The Oceans Tell Us About Ourselves" (ph). And he helped found a research initiative to investigate how sperm whales communicate with each other through clicks.

James Nestor, welcome to FRESH AIR. How are you?

Want to listen to the podcast?

JAMES NESTOR: Doing very well. Thanks so much for having me.

GROSS: Has your research into breathing taking on a slightly different meaning because of COVID-19, because of its respiratory systems and the anxiety that it's creating?

NESTOR: I think the awareness of breathing has definitely increased. When I first started this research several years ago, a lot of my friends were saying, you're writing a book about breathing? I've been breathing my whole life. Why would you want to write a book about that? But now these are the same friends who are seeing how essential respiratory health is in helping us both prevent the onset of many illnesses and to help us get through illnesses like COVID - to help us better get through them.

GROSS: So you had been a mouth breather, and you did some snoring. You had a deviated septum, which was affecting your ability to breathe through your nose because that kind of clogs part of the nose - or blocks part of the nasal passage, I should say. So to understand whether mouth breathing was really a problem, you participated in a study at Stanford University that forced you to breathe through your mouth. Describe what the setup was.

NESTOR: Yeah. So I had been in contact with the chief of rhinology research, Jayakar Nayak, for months and months. We had had several interviews. We'd been talking a lot. And he was telling me all the wonders of nasal breathing and how bad mouth breathing was. And none of that was controversial. That's very well-established now. But nobody really knew how - all the problems of mouth breathing - no one knew how soon those came on.

So I asked him. I said, well, why don't you test it? You're in a position to test it. He's like, how am I going to test it? It would be unethical to ask someone to plug their nose for a certain amount of time and measure what happens. And I said, well, I'll do it. So it was never, like, a "Super Size Me" study. That wasn't our intention. If - 25 to 50% of the population is breathing through their mouth, so I was just lulling myself into a condition I already knew and that so many other people already knew.

So the plan was, for 10 days, I would have silicone plugs up my nose - me and one other subject, a breathing therapist from Sweden; I convinced him to do this study as well. And for the other 10 days, we would change the pathway of how we breathe and breathe through our noses instead of our mouths. So that was it. That was the setup. And you know, we thought that mouth breathing for 10 days was going to be bad, but we had no idea it was going to be so damaging.

GROSS: How bad was it?

NESTOR: (Laughter) Well, I went from snoring a couple minutes a night to - within three days, I was snoring for hours a night. I developed sleep apnea. My stress levels were off the charts. My nervous system was a mess. We had a whole home lab here at my house, so we were testing each other three times a day every day and writing out all of these metrics. We even had - were looking at blood glucose, how that was affected.

So I felt awful. I felt fatigued - snoring, sleep apnea, all the rest - and even performance - athletic performance really decreased as well. And the good thing about this is, I was able to take these god-awful plugs out of my nose and breathe nasally again. And once I did that, snoring disappeared; sleep apnea disappeared; nervous system came back into balance - I mean, completely transformed by just changing the pathway through which we breathed.

GROSS: So what's in the nose that makes nose breathing better than mouth breathing 'cause mouths don't have that stuff?

NESTOR: So the nose filters heat and treats raw air. Most of us know that. But so many of us don't realize - at least, I didn't realize - how it can trigger different hormones to flood into our bodies, how it can lower our blood pressure, how the stages of a woman's menstrual cycle are correlated to different areas of the nose, how it monitors heart rate - on and on and on - even helps store memories. So it's this incredible organ that is not represented in any of the departments of the National Institutes of Health, and this is something that Nayak has, you know, just hammered down over and over again. He's like, why aren't we studying this more? And why don't people - more people realize how important nasal breathing is? So it's - it orchestrates innumerable functions in our body to keep us balanced.

GROSS: What I found most surprising was that the nose actually has erectile tissue like men's and women's genitals.

NESTOR: (Laughter) So the nose is more closely connected to our genitals than any other organ. So it is covered in that same tissue. So when one area gets stimulated, the nose will become stimulated as well. Some people have too close of a connection, where they get stimulated in the southerly regions - they will start uncontrollably sneezing. And this condition is common enough that it was given a name called honeymoon rhinitis. So the...

GROSS: Wow (laughter).

NESTOR: That - the - yeah. This is the weird stuff you never thought you'd discover when you start writing a book about breathing. But another thing that is really fascinating is, that erectile tissue will pulse on its own, so it will close one nostril and allow breath in through the other nostril. Then that other nostril will close and allow breath in. And our bodies do this on their own, and this switching happens between 30 minutes and every three hours.

And a lot of people think - a lot of people who have studied this believe that this is the way that our bodies maintain balance because when we breathe through our right nostril, circulation speeds up; the body gets hotter; cortisol levels increase; blood pressure increases. So breathing through the left will relax us more, so blood pressure will decrease - lowers temperature, cools the body, you know, reduces anxiety as well. So our bodies are naturally doing this. And when we breathe through our mouths, we're denying our bodies the ability to do this and to keep us in balance.

GROSS: But what about if you can't breathe through your nose because either you have a cold or a respiratory illness or you have a bad deviated septum?

NESTOR: Sure. Around 70% of the population has a deviated septum that's clearly visible to the naked eye. So this is just rampant. And I certainly do. When I got a CAT scan of my head, it was an absolute mess. But some conditions are so severe that you will need surgical intervention for sure. But the vast majority are not. And something Nayak kept telling me is, he said, you know, if a sink is clogged in your house, you're going to find a way of unclogging it. The nose should be considered in the same way.

For noses clogged, you need to find a way of unclogging it. You can do that by breathing more through your nose because it's really a use-it-or-lose-it organ. The more you breathe through it, the more you're going to be able to breathe through it. I was just talking to a clinician who's trained something like 7,000 people to nasal breathe. And only four of them could not breathe through their noses after about three weeks of training. So it's really something - the more we focus on it, the more we really concentrate, the more we're able to open it up and to get all those benefits of nasal breathing.

GROSS: So after you do this experiment about breathing exclusively for your - through your mouth, you decided, at night, to try taping your mouth so that you couldn't breathe through your mouth and you'd have to breathe through your nose. How did that go?

NESTOR: (Laughter) Yeah. So this is something - a hack that I had heard about and was extremely skeptical about. It sounded very dangerous to me until I talked to a breathing therapist at Stanford, who said that she had cured her own mouth-breathing by taping her mouth at night, and until I talked to a dentist, who'd been in the field for 20, 30 years who prescribes this to his patients.

Now, I'm not talking about getting a fat piece of duct tape and taping that over your mouth. That's a really bad idea. I'm talking about a teeny piece of surgical tape about the size of a stamp. Imagine, like, a Charlie Chaplin mustache moved down an inch. And my personal experience with this is it has allowed me to sleep so much better, wake up so much more rested and to not have that dry mouth every morning.

GROSS: So with the kind of tape you're talking about, if your mouth really needed to open, it could because that's not - like you said, it's not, like, really strong tape. It's just, like, surgical tape and a little piece of it. So you're not...

NESTOR: Of course.

GROSS: You're not gagging yourself (laughter).

NESTOR: Yeah. And I'm not prescribing - I'm not qualified to...

GROSS: And you're not prescribing it, and neither am I (laughter).

NESTOR: I'm not prescribing anything. No, no, no.

GROSS: Yeah. Yeah.

NESTOR: I'm saying, this personally worked for me. But don't go on YouTube. Don't go on the Internet and see these people with nine pieces of tape over their lower jaw. It's like, bad idea. I've found all you need is a very small piece of tape. And there's even a product out right now that is being sold as a remedy for snoring. And what is it? It's a piece of tape that you put on your lips at night (laughter). So other people - and they've conducted studies to show how effective it is. So this worked well for me. It's worked well for many other people. But I'm not prescribing anything.

GROSS: And I should mention that my guest, James Nestor, is also not a doctor. He's a journalist. And he's reporting on what he's learned by talking to many researchers and doctors and people who practice breathing techniques and teach breathing techniques. If you're just joining us, my guest is journalist James Nestor, author of the new book "Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art." We'll talk more after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF GERALD CLAYTON'S "ENVISIONINGS")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with journalist James Nestor, author of the new book, "Breath," about what ancient forms of Eastern meditation, as well as new science, tell us about breathing and how, by controlling our breath through various techniques, we can improve our sleep, our health and decrease our anxiety.

Breathing is automatic. But we can control, when we consciously try, the quality of the breath, the length of inhales and exhales, and how deeply or shallowly we breathe. Can you explain why breath would, for instance, affect anxiety and how breathing in certain ways, certain breathing techniques, can decrease anxiety...

NESTOR: Sure.

GROSS: ...Anxiety being a very important subject right now.

NESTOR: So for so many of us, we think that it's just important that we're breathing because if we're breathing, that's good. That means we're alive. If we're not breathing, that's bad, you know, we could be dead. But it's how we take those breaths. We take 25,000 breaths a day. And 30 pounds of air enters and exits our lungs every day. So it's how we take those breaths and the nuances of those breaths that I've found play such an important role in health, happiness and longevity.

So specifically, with anxiety, talked to a neuropsychologist, went out to his lab at the Laureate Institute of Brain Research. And he explained to me that people with anxieties or other fear-based conditions, typically, will breathe way too much. So what happens when you breathe that much is you're constantly putting yourself into a state of stress. So you're stimulating that sympathetic side of the nervous system.

And the way to change that is to breathe deeply, because if you think about it, if you're stressed out - a tiger is going to come get you, you know, you're going to get hit by a car - you're going to breathe, breathe, breathe as much as you can. But by breathing slowly, that is associated with a relaxation response. So the diaphragm lowers. You're allowing more air into your lungs. And your body immediately switches to a relaxed state.

So we may not be able to control the function of our hearts, other organs in our body, but we can control our breathing. And when we control our breathing, we can influence so much of how our bodies operate. And that includes - as a treatment or at least a practice for people with anxieties, depression, just changing their breathing, psychiatrists have found, can have a very transformational effect. It seems so simple to be true. But some of these people have been studying this subject for decades. And that's what they've found.

GROSS: There are many different breathing techniques. There are many different breathing meditation styles. What do they all have in common? Is there something they all have in common in terms of inhale and exhale and the basic principles underneath?

NESTOR: So breathing has been studied for thousands and thousands of years. There are seven books of the Chinese Tao that deal only with breathing, what happens when we do it improperly and all of the benefits we can get by doing it properly. So all of those ways, all of the different practices do have one thing in common. And that's because they allow you to slow down and consciously listen to yourself and feel how breath is affecting you. So there is many different tools in this toolbox. If you want to slow down and become more relaxed, you can exhale longer than you inhale. So that will have a very powerful effect on you for relaxation.

If you want to stimulate yourself and get going, you can breathe much faster. So what I've found is, throughout time, throughout millennia, these different cultures at different times, different peoples were discovering the same exact thing over and over. So it's very interesting that, right now, we have the science and the techniques and measurements to really prove what these people have been saying for so long.

GROSS: Why does the exhale quiet the system?

NESTOR: Because the exhale is a parasympathetic response. Right now, you can put your hand over your heart. And if you take a very slow inhale in, you're going to feel your heart speed up. As you exhale, you should be feeling your heart slow down. So exhaling relaxes the body. And something else happens when we take a very deep breath like this. So the diaphragm lowers. When we take a breath in. And that sucks a bunch of blood, a huge profusion of blood, into the thoracic cavity.

As we exhale, that blood shoots back out through the body. So the diaphragm is considered the second heart because it plays such a huge role in circulation. And it lowers the burden of the heart if we breathe properly and if we really engage the diaphragm. So these slow and low breaths, people should be practicing these as much as possible. This is the way your body wants to take an air.

GROSS: If you want to start breathing to calm yourself down, do you have any suggestions for the length of the inhale and the length of the exhale?

NESTOR: Sure. And this was a study I'd stumbled upon that's about 20 years old now, that some Italian researchers gathered a group of subjects. And they had them recite the Ave Maria, so the Catholic prayer cycle. And then they had them recite om mani padme hum, which is a Buddhist prayer. What they found is that it took about 5 1/2 seconds to recite each of these prayers, and then about 5 1/2 seconds to then inhale.

And so by breathing about 5 1/2 seconds out, 5 1/2 seconds in, they found that blood to the brain increased. The body entered this state of balance in which all of the organs, all of the system worked in harmony with one another. And they covered these people with sensors and were able to see all of this all on data sheets. And the study is widely available. So they later found that you don't need to really pray to get these benefits even though you can do that if you'd like.

But just by breathing at this rate, about 5 1/2 seconds in, 5 1/2 seconds out - don't worry if you're a second off, you know, the point is to relax yourself - you are able to get the perfect amount of air into your body and out of your body and really allow your body to do what it's naturally designed to do, which is function with the least amount of effort. And they've taught this breathing - psychiatrists have taught this breathing pattern to people with anxiety, depression, even 9/11 survivors who had this ghastly condition called ground-glass lungs. And it had significant effects on them by just breathing this way.

GROSS: You've said if you exhale longer than you inhale, that that can be very calming. So if both the inhale and the exhale are 5 1/2 seconds, you're not doing a longer exhale. Does that matter?

NESTOR: So the body wants to be balanced, right? We want sympathetic balance. We want parasympathetic balance. So just in regular day-to-day activity, you want to have that balance. Before you go to sleep, you can extend that exhale and become more relaxed. But I would not be extending that exhale before a meeting or before an important phone call.

So you can use these different tools to do different things. You can also inhale longer and exhale shorter if you want a little boost of energy. So the even-steven, like, the most balanced way of breathing that I've found after studying this stuff and talking to the leaders in the field was that five to six seconds in, five to six seconds out.

GROSS: My guest is journalist James Nestor, author of the new book "Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art." We'll talk more after we take a short break. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF FRED KATZ'S "FOGGY, FOGGY DEW")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with journalist James Nestor, author of the new book "Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art." It's about the impact of how we breathe on our health, our sleep and our anxiety level. He investigates different ancient and new breathing techniques that can improve our health and expand our lung capacity. Nestor's previous book, "DEEP," was about free diving, in which divers go deep underwater, for up to 12 minutes, on one breath.

James, you know, in talking about breath and its impact on our health and our anxiety, you referred to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. Without going into too much detail, can you just explain briefly what each of them are and why they're relevant to breath?

NESTOR: Sure. The sympathetic nervous system is the system that triggers a fight-or-flight reaction. So when we sense danger, the sympathetic nervous system switches on, floods our bodies with stress hormones and allows us to become meaner and leaner and to fight harder or to run really fast. That's what that does.

So the parasympathetic is the opposite. This is the side of the nervous system that triggers a rest-and-relax response. And we want to be in this state when we're eating food. Mostly, throughout the entire day, we want to be in a parasympathetic state. The problem is that, nowadays, all of us are kind of half-stressed. We're not really running away from a tiger or a lion or fighting for our lives, but we're not really relaxing, either. So we're staying in this gray zone, where during the night, we're half-awake and during our days, we're half-asleep.

So that's what I found was so interesting about breathing, is by just breathing, you can elicit these different nervous system states. So you can take command of something that was supposed to be autonomic. That's what it's called - the autonomic nervous system. But you can control it, and you can stress yourself out if you want, or you can relax yourself, just by breathing.

GROSS: What are the things that we typically do wrong when we breathe? Like, speaking for myself, I think I'm a very shallow breather when I'm not paying attention to my breathing. I think my kind of go-to state is just shallow breaths. So what's wrong with that?

NESTOR: Well, you can think about breathing as being in a boat, right? So you can take a bunch of very short, stilted strokes, and you're going to get to where you want to go. It's going to take a while, but you'll get there. Or you can take a few very fluid and long strokes and get there so much more efficiently. So your body doesn't want to be overworked all the time because, if it is, then things start to break down.

So you want to make it very easy for your body to get air, especially if this is an act that we're doing 25,000 times a day. So by just extending those inhales and exhales, by moving that diaphragm up and down a little more, you can have a profound effect on your blood pressure, on your mental state, on - even on longevity because so much of longevity is correlated with respiratory health and lung size.

GROSS: One of the trips that you took as part of your research was to Philadelphia to go to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and look at their skull collection with Dr. Marianna Evans. And she told you some fascinating things about how the skull has changed through human history - I mean through the evolution (laughter) of human history and how the nose has changed. So tell us some of the most interesting things you learned about how our nose evolved.

NESTOR: So - sure. You know, when I was first starting out researching this book, I thought I had a pretty good idea of where all of the research was going to lead me. I identified the leaders in the field, different areas I was going to go into.

But about six months into it, I realized that so much of what I had planned had to be thrown out because there was a much stranger story several layers deep. And it was the fact that so many of us are breathing poorly not because some sort of psychological problem, not because we're anxious, but because we can't, because our skulls have changed so much, especially in the last 400 years, that it's blocked our sinuses, and it's made us breathe more through our mouths.

And at the beginning, when I heard this, I didn't believe it. But I started talking to biological anthropologists who kept telling me the same thing over and over. They said if you take a skull that's a thousand years old and compare it to a new skull, that skull that's a thousand years old, there's a very good chance its teeth are going to be perfectly straight, whereas the modern skull, there's a very good chance its teeth are going to be very crooked.

So those perfectly straight teeth in that thousand-year-old skull, they would be the same teeth you'd find in a 10,000-year-old skull, hundred-thousand-year-old skull and on back. So just in the past 400 years, humans now have - about 90% percent of us - have some problems with our teeth that make them grow in crooked. And the reason is our mouths have grown so small that our teeth have nowhere to go. So they come in crooked. And another problem with having too small of a mouth is it also gives us too small of an airway to easily take air in and out.

So this was a story about evolution I never heard about in school, that I didn't think could be possibly true, unless you start looking at skulls. So she welcomed me, Marianna Evans, to go to the museum with the largest collection of preindustrial skulls. And time in, time out, didn't matter if the skulls were coming from Asia or Africa or South America, they all had straight teeth. And if you - again, if you look at a skull now, it's a very good chance it's going to have crooked teeth.

GROSS: So the obvious question is, why did skulls get smaller?

NESTOR: Well, I think that - you know, I had learned in school that evolution always meant survival of the fittest. But it doesn't; it means change. And life forms can change for the better or worse, and humans have certainly been changing in ways that are a detriment to our health. And this change, this catalyst that caused our mouths to go smaller, is tied to industrial food. It's not vitamins and minerals, as many people would suspect; it's chewing. The fact is, for the past 300 years, our food has been so processed, so soft, that we're not chewing anymore. So our mouths never quite develop right, which means our airways are clogged.

GROSS: Didn't Dr. Evans also tell you that as the human brain expanded, it left less room for the nose and the mouth?

NESTOR: This was about a million years ago, when we started processing foods, bashing prey against rocks. And we started cooking foods about 800,000 years ago, our brains started growing so rapidly, and they needed real estate. So they took it from the front of our faces, and they took it from our mouths. But these changes happened over tens of thousands of years, these morphological changes. So the changes that happen to our mouths happen very quickly, and we haven't been able to adapt fast enough to really acclimate to it.

So that is one of the reasons why we have so many chronic breathing problems. It's tied to the shrinking of the front of our faces.

GROSS: Well, let me take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is journalist James Nestor, author of the new book "Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art." We'll talk more after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with journalist James Nestor, author of the new book "Breath," about what ancient forms of Eastern meditation as well as new science tell us about breathing and how, by controlling our breath through various techniques, we can improve our sleep, our health and decrease our anxiety.

So you had respiratory problems 10 years ago, when you started all this research into breathing techniques. Have your respiratory problems improved?

NESTOR: I have not had pneumonia since I've been using these techniques. I haven't had bronchitis. I've been breathing clearly through my nose. I've had one stuffed nose in the past year and a half, when I came down with a flu. So I'm not using that as confirmed data that says this stuff works; I'm saying that it worked for me.

And I just want to also make clear that I had no slant going into this world. My job, as a journalist who writes about science a lot, is to take all the data, talk to as many people as I can and come out with a very objective view of what's going on here. That's what I really tried to do with this book. So I don't want to be preaching slow breathing or heavy breathing or whatever. I wanted to present the facts and the studies and say, this is what's worked for people; this is what the science says.

But on a personal point, you know, I will say, you get pretty emotionally invested in the subject once you've been in it for years and years. And once you've seen these people so profoundly transformed, the more you dive into these worlds and become consumed by it, the more you want to feel these benefits and try to understand them in a certain way so you can relay that back to the reader.

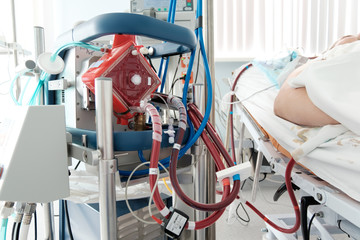

GROSS: You know, so many doctors now are trying to figure out how the coronavirus works in the body and why it does the damage that it does and how they can help patients, you know, get over it and recover. And I know that some doctors now, instead of using respirators, are doing what's called proning, in which the person who is having the breathing problems because of the virus, instead of lying on their back, they lay on their side or, I think, on their chest, and that that seems to somehow make it easier for them to breathe. And I'm wondering if you have been reading about that and what your understanding of it is.

NESTOR: So about four weeks ago, five weeks ago, when a patient would have very severe symptoms of COVID, they would bring them in and lay them on their back and sometimes intubate them, and this seemed to work for a lot of the patients. But what they found more recently was that by laying them on their sides or on their stomachs, they could breathe so much better.

I found this was so interesting because 2,000 years ago, Chinese doctors prescribed side-sleeping as well. And then you have a cardiologist 80 years ago, 70 years ago, named Buteyko that asked all of his patients with pneumonia or other respiratory problems to always sleep on their sides. So he would even tape balls to their back so they could not sleep on their backs. So it seems like this science that has been around for hundreds, sometimes thousands of years just keeps popping up in these different ways.

And they've found that prone breathing - and they've even put some patients in a chair because they don't want them lying down - is extremely effective. And a lot of this has to do with how we breathe. When you take a big breath, your back is - more of the lungs are on your back, so your back is going to be expanding. Your chest expands a little bit, but most of that is happening at the back. So when you're lying someone on their backs, they're not going to be able to access their lungs as efficiently.

So it's simple physics. By flipping them around, they're going to be able to breathe better. So this was just another example. I was sending this back and forth to my father-in-law, who's a pulmonologist, been a pulmonologist for 40 years. And I was just like, it's more of the new science of a lost art here. We're just rediscovering all of these hacks that have been around for so long.

GROSS: I didn't realize your father-in-law was a pulmonologist, which means he works with patients who have lung issues. What does he make of the research that you present in the book? Is it consistent with what he's found as a doctor? And I'm wondering if he's adding anything to his toolbox (laughter).

NESTOR: All I can say is we've had some very lively Thanksgiving dinners together talking about this stuff over the years.

GROSS: (Laughter).

NESTOR: But at the beginning, he thought a lot of what I was uncovering - he was like, I never heard of that; I don't know about this. He's a pretty conservative guy in his beliefs, as far as medicine is concerned.

But over the years, one of the most fascinating things for me has been presenting him with more of this research, more of these studies, more of these investigators and scientists who have been saying the same stuff and watching him really change his mind. That's not what I set out to do. I want him to be critical and trust me. He was when I was bringing up a lot of these issues.

But watching him come around and get very exciting about using these other hacks, especially now, especially with COVID, when so many of us aren't breathing well - we've got masks on; we feel tightness in our chest - to be able to focus on our breathing and really allow us to be healthier and to have more of a calmer state of mind. So it's been a fantastic conversation over several years, and he's very excited about some of this really weird stuff I've uncovered.

GROSS: You know, your previous book was about divers who dive deep with one breath, and they can hold one breath for about 12 minutes. How do they train their lungs to expand enough to hold enough air to do all that on one breath?

NESTOR: So the world record is 12 1/2 minutes, the breath-hold. And most divers will hold their breath for eight minutes or seven minutes, which is still incredible to me. When I first saw this - this was several years ago. I was sent out on a reporting assignment to write about a free-diving competition. You watch this person at the surface take a single breath of air and completely disappear into the ocean, come back five or six minutes later. So

the way they were able to do this was by breathing.

So we've been told that whatever we have, whatever we're born with is what we're going to have for the rest of our lives, especially as far as the organs are concerned. But we can absolutely affect our lung capacity. So some of these divers have a lung capacity of 14 liters, which is about double the size for a regular adult male. So they weren't born this way. This was something they did through will. They train themselves to breathe in ways to profoundly affect their physical bodies.

GROSS: So one of the things that you do is you work with a project to try to understand how whales communicate with each other through their clicks. And this is related to the book that you did on free divers 'cause the book is also about oceans and what we can learn from oceans. So the group is called CETI - not like the extraterrestrial S-E-T-I group. But this is C-E-T-I. I'm afraid to say CETI because I think people will think you're trying to communicate with extraterrestrials.

NESTOR: Well, we're trying to communicate with nonhuman species, so it's very similar in some ways. You know, a number of years ago, I saw the real benefits of free diving, and it wasn't to best a competitor and dive down the deepest and come back. It was to really allow yourself to become a part of the underwater environment because when you're free diving, and you're holding your breath at 50, hundred feet down, you become a living and nonbreathing part of everything around you. So instead of animals swimming away from you as they would with scuba, they swim towards you, and they welcome you into their shoals or pods.

So after seeing free divers do this, that was the main impetus for me wanting to focus my breathing and learn to free dive - was to commune and get in touch with these animals. So we targeted sperm whales, who are the largest toothed predators on the planet, and they can grow as long as a school bus. And it turns out that these animals share this very sophisticated form of communication through these clicks. It's almost like a Morse code type of communication.

So by free diving with them and not hanging around them with a boat, which they don't like, or scuba, which they don't like, they welcomed you in and started clicking at you. And this was one of the most powerful experiences I've ever had, to be in the water with this animal that's the size of a school bus that at any time could kill me, could chew me up with its 8-inch-long teeth or hit me with its fluke but chose not to, but chose to come in peace and send out these little clicks. And it just got me thinking, how wonderful would it be for us to understand these clicks and perhaps one day talk back with these animals?

So this was an experience I had so many years ago, but it continues to stick with me. And I was lucky enough to meet David Gruber, who is a marine biologist, and we've been working away for years to put a program together to use machine learning and AI to look into this communication and to try to perhaps one day crack it and learn more about these fantastic animals.

GROSS: James Nestor is the author of the new book "Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art." After we take a short break, Kevin Whitehead will review a new jazz recording of Transylvanian folk songs that were collected and transcribed by Bela Bartok. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Original article by NPR.